|

The Gaze: Systems of Observation: Physical Intellectual Emotional Spiritual Aesthetic Scientific others Photography Composition Tutorial http://compofoto.lluisribes.net/en/

All in how you look at the world:

Seeing and recording life around you the good, the

bad and the ugly: Scale: teenage series: http://juliafullerton-batten.com/ ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: The future https://www.digitalcameraworld.com/news/camera-rumors ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: Excellent Photography Websites: Going off

Automatic by Oliva Robinson Depth of Field This is the link to the depth of field calculator which

tells you exactly how much of a scene will be in focus based on the focal

length, distance from the object, aperture, and camera sensor size Great source of info to keep in mind from: Learning about

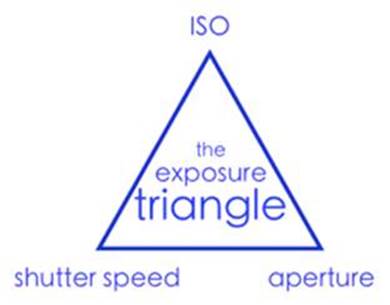

Exposure – The Exposure Triangle

In

it Bryan illustrates the three main elements that need to be considered when

playing around with exposure by calling them ‘the exposure triangle’. Each

of the three aspects of the triangle relate to light and how it enters and

interacts with the camera. The

three elements are:

It

is at the intersection of these three elements that an image’s exposure is

worked out. Most

importantly – a change in one of the elements will impact the others. This

means that you can never really isolate just one of the elements alone but

always need to have the others in the back of your mind. 3

Metaphors for understanding the digital photography exposure triangle: Many

people describe the relationship between ISO, Aperture and Shutter Speed

using different metaphors to help us get our heads around it. Let me share

three. A quick word of warning first though – like most metaphors – these are

far from perfect and are just for illustrative purposes: The

Window Imagine

your camera is like a window with shutters that open and close. Aperture

is the size of the window. If it’s bigger more light gets through and the

room is brighter. Shutter

Speed is the amount of time that the shutters of the window are open. The

longer you leave them open the more that comes in. Now

imagine that you’re inside the room and are wearing sunglasses (hopefully

this isn’t too much of a stretch). Your eyes become desensitized to the light

that comes in (it’s like a low ISO). There

are a number of ways of increasing the amount of light in the room (or at

least how much it seems that there is. You could increase the time that the

shutters are open (decrease shutter speed), you could increase the size of

the window (increase aperture) or you could take off your sunglasses (make

the ISO larger). Ok

– it’s not the perfect illustration – but you get the idea. Sunbaking Another

way that a friend recently shared with me is to think about digital camera

exposure as being like getting a sun tan. Now

getting a suntan is something I always wanted growing up – but unfortunately

being very fair skinned it was something that I never really achieved. All I

did was get burnt when I went out into the sun. In a sense your skin type is

like an ISO rating. Some people are more sensitive to the sun than others. Shutter

speed in this metaphor is like the length of time you spend out in the sun.

The longer you spend in the sun the increased chances of you getting a tan

(of course spending too long in the sun can mean being over exposed). Aperture

is like sunscreen which you apply to your skin. Sunscreen blocks the sun at

different rates depending upon it’s strength. Apply

a high strength sunscreen and you decrease the amount of sunlight that gets

through – and as a result even a person with highly sensitive skin can spend

more time in the sun (ie decrease the Aperture and

you can slow down shutter speed and/or decrease ISO). As

I’ve said – neither metaphor is perfect but both illustrate the interconnectedness

of shutter speed, aperture and ISO on your digital camera. Update:

A third metaphor that I’ve heard used is the Garden Hose (the width of the

hose is aperture, the length that the hose is left on is shutter speed and

the pressure of the water (the speed it gets through) is ISO. :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: Aperture

Before

I start with the explanations let me say this. If you can master aperture you

put into your grasp real creative control over your camera. In my opinion –

aperture is where a lot of the magic happens in photography and as we’ll see

below, changes in it can mean the difference between one dimensional and multi dimensional shots. What

is Aperture? Put

most simply

– Aperture is ‘the size of the opening in the lens when a picture is taken.’ When

you hit the shutter release button of your camera a hole opens up that allows

your cameras image sensor to catch a glimpse of the scene you’re wanting to

capture. The aperture that you set impacts the size of that hole. The larger

the hole the more light that gets in – the smaller

the hole the less light. Aperture

is measured in ‘f-stops’. You’ll often see them referred to here at Digital

Photography School as f/number – for example f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6,f/8,f/22 etc.

Moving from one f-stop to the next doubles or halves the size of the amount

of opening in your lens (and the amount of light getting through). Keep in

mind that a change in shutter speed from one stop to the next doubles or

halves the amount of light that gets in also – this means if you increase one

and decrease the other you let the same amount of light in – very handy to keep

in mind). One

thing that causes a lot of new photographers

confusion is that large apertures (where lots of light gets through) are

given f/stop smaller numbers and smaller apertures (where less light gets

through) have larger f-stop numbers. So f/2.8 is in fact a much larger

aperture than f/22. It seems the wrong way around when you first hear it but

you’ll get the hang of it. Depth

of Field and Aperture There

are a number of results of changing the aperture of your shots that you’ll

want to keep in mind as you consider your setting but the most noticeable one

will be the depth of field that your shot will have. Depth

of Field (DOF) is that amount of your shot that will be in focus. Large

depth of field means that most of your image will be in focus whether

it’s close to your camera or far away (like the picture to the left where

both the foreground and background are largely in focus – taken with an

aperture of f/22). Small

(or shallow) depth of field means that only part of the image will be in

focus and the rest will be fuzzy (like in the flower at the top of this post

(click to enlarge). You’ll see in it that the tip of the yellow stems are in focus but even though they are only 1cm or so

behind them that the petals are out of focus. This is a very shallow depth of

field and was taken with an aperture of f/4.5). Aperture

has a big impact upon depth of field. Large aperture (remember it’s a smaller

number) will decrease depth of field while small aperture (larger numbers)

will give you larger depth of field. It

can be a little confusing at first but the way I remember it is that small

numbers mean small DOF and large numbers mean large DOF. Let

me illustrate this with two pictures I took earlier this week in my garden of

two flowers.

The

f/2.8 shot (2nd one) has the left flower in focus (or parts of it) but the

depth of field is very shallow and the background is thrown out of focus and

the bud to the right of the flower is also less in focus due to it being

slightly further away from the camera when the shot was taken. The

best way to get your head around aperture is to get your camera out and do

some experimenting. Go outside and find a spot where you’ve got items close

to you as well as far away and take a series of shots with different aperture

settings from the smallest setting to the largest. You’ll quickly see the

impact that it can have and the usefulness of being able to control aperture. Some

styles of photography require large depths of field (and small Apertures) For

example in most landscape photography you’ll see small aperture settings

(large numbers) selected by photographers. This ensures that from the

foreground to the horizon is relatively in focus. On

the other hand in portrait photography it can be very handy to have your

subject perfectly in focus but to have a nice blurry background in order to

ensure that your subject is the main focal point and that other elements in

the shot are not distracting. In this case you’d choose a large aperture

(small number) to ensure a shallow depth of field. Macro

photographers tend to be big users of large apertures to ensure that the

element of their subject that they are focusing in on totally captures the

attention of the viewer of their images while the rest of the image is

completely thrown out of focus. Read

more: http://digital-photography-school.com/aperture#ixzz2MSOfQo2W :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: What is Shutter

Speed? As

I’ve written elsewhere, defined most basically – shutter speed is ‘the

amount of time that the shutter is open’. In

film photography it was the length of time that the film was exposed to the

scene you’re photographing and similarly in digital photography shutter speed

is the length of time that your image sensor ‘sees’ the scene you’re

attempting to capture. Let

me attempt to break down the topic of “Shutter Speed” into some bite sized

pieces that should help digital camera owners trying to get their head around

shutter speed: • Shutter speed is measured in seconds

– or in most cases fractions of seconds. The bigger the denominator the

faster the speed (ie 1/1000 is much faster than

1/30). • In most cases you’ll probably be

using shutter speeds of 1/60th of a second or faster. This is because

anything slower than this is very difficult to use without getting camera

shake. Camera shake is when your camera is moving while the shutter is open

and results in blur in your photos. • If you’re using a slow shutter speed

(anything slower than 1/60) you will need to either use a tripod or some some type of image stabilization (more and more cameras

are coming with this built in). • Shutter speeds available to you on

your camera will usually double (approximately) with each setting. As a

result you’ll usually have the options for the following shutter speeds –

1/500, 1/250, 1/125, 1/60, 1/30, 1/15, 1/8 etc. This ‘doubling’ is handy to

keep in mind as aperture settings also double the amount of light that is let

in – as a result increasing shutter speed by one stop and decreasing aperture

by one stop should give you similar exposure levels (but we’ll talk more

about this in a future post). • Some cameras also give you the

option for very slow shutter speeds that are not fractions of seconds but are

measured in seconds (for example 1 second, 10 seconds, 30 seconds etc). These are used in very low light situations, when

you’re going after special effects and/or when you’re trying to capture a lot

of movement in a shot). Some cameras also give you the option to shoot in ‘B’

(or ‘Bulb’) mode. Bulb mode lets you keep the shutter open for as long as you

hold it down. • When considering what shutter speed

to use in an image you should always ask yourself whether anything in your

scene is moving and how you’d like to capture that movement. If there is

movement in your scene you have the choice of either freezing the movement

(so it looks still) or letting the moving object intentionally blur (giving

it a sense of movement). • To freeze movement in an image (like

in the surfing shot above) you’ll want to choose a faster shutter speed and

to let the movement blur you’ll want to choose a slower shutter speed. The

actual speeds you should choose will vary depending upon the speed of the

subject in your shot and how much you want it to be blurred. • Motion is not always bad – I spoke to

one digital camera owner last week who told me that he always used fast

shutter speeds and couldn’t understand why anyone would want motion in their

images. There are times when motion is good. For example when you’re taking a

photo of a waterfall and want to show how fast the water is flowing, or when

you’re taking a shot of a racing car and want to give it a feeling of speed,

or when you’re taking a shot of a star scape and want to show how the stars

move over a longer period of time etc. In all of these instances choosing a

longer shutter speed will be the way to go. However in all of these cases you

need to use a tripod or you’ll run the risk of ruining the shots by adding

camera movement (a different type of blur than motion blur). • Focal Length and Shutter Speed -

another thing to consider when choosing shutter speed is the focal length of

the lens you’re using. Longer focal lengths will accentuate the amount of

camera shake you have and so you’ll need to choose a faster shutter speed

(unless you have image stabilization in your lens or camera). The ‘rule’ of

thumb to use with focal length in non image

stabilized situations) is to choose a shutter speed with a denominator that

is larger than the focal length of the lens. For example if you have a lens

that is 50mm 1/60th is probably ok but if you have a 200mm lens you’ll

probably want to shoot at around 1/250. Shutter

Speed – Bringing it Together Remember

that thinking about Shutter Speed in isolation from the other two elements of

the Exposure Triangle (aperture and ISO) is not really a good idea. As you

change shutter speed you’ll need to change one or both of the other elements

to compensate for it. For

example if you speed up your shutter speed one stop (for example from 1/125th

to 1/250th) you’re effectively letting half as much light into your camera.

To compensate for this you’ll probably need to increase your aperture one

stop (for example from f16 to f11). The other alternative would be to choose

a faster ISO rating (you might want to move from ISO 100 to ISO 400 for

example). :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: Action shots Tv (Time value) shutter –priority on the mode dial see: light painting ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; Experiment: using a tripod take an image of a

moving event at various shutter speeds such as 1 second, 1/3, 1/30, 1/200, 1/800.

Explore your results. What happens to the way movement appears in your

photographs? What happens to the background of your image? Shutter

speed along with the aperture of the lens (also called f-number) determines

the amount of light that reaches the film or sensor. Conventionally, the

exposure is measured in units of exposure value (EV), sometimes called stops,

representing a halving or doubling of the exposure. Multiple

combinations of shutter speed and aperture can give the same exposure: halving

the shutter speed doubles the exposure (1 EV more), while doubling the

aperture size (halving the focal number) increases the exposure area by a

factor of 4 (2 EV). For this reason, standard apertures differ by √2,

or about 1.4. Thus an exposure with a shutter speed of 1/250 s and f/8 is the

same as with 1/500 s and f/5.6, or 1/125 s and f/11. Think

in terms of capturing existing moving events or staging moving events of your

own… be creative, experiment and feel the motion reflected in the image ! Slow

shutter speed combined with panning the camera can achieve a motion blur for

moving objects. What is Panning? Panning

is the horizontal movement of a camera as it scans a moving subject. When

you pan you’re moving your camera in synchronicity with your subject as it

moves parallel to you. Still a little wordy huh? It’s not as

complicated as it sounds. Shake your head “no.” Go on and do it.

Now cut that in half and pretend like you’re moving you head along with a

cheetah as is it flies by and you’ve got the idea. In order to pan

successfully your camera has got to follow the subject’s movement and match it’s speed and direction as perfectly as possible. What’s

it for? Proper

panning implies motion. However, panning creates the feeling of motion and

speed without blurring the subject as a slow shutter speed sans panning would

tend to do. Take for example the two images below. The first is

an example of panning. Notice how the car is clear and crisp but the

rest of the image is blurred to show the motion of the vehicle. This

effect was achieved by panning.

Image

Credit: Blentley

Now

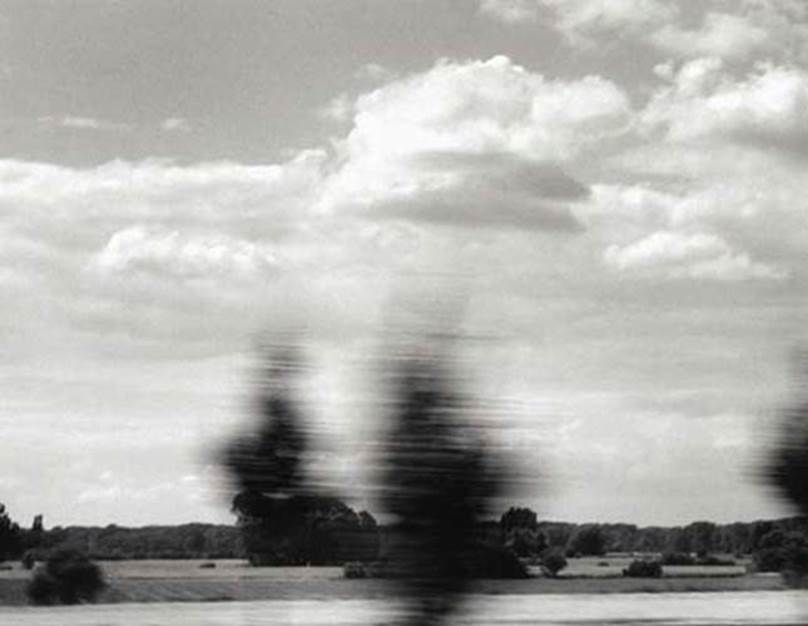

check out the second image. This is an

example of a slow shutter speed (which panning also requires by the way)

without the panning of the camera.

Because the camera was held static, the moving object, in this case

the train, depicts the motion while the area around it is static. Image

Credit: Papalars Is

one image better than the other?

Maybe, maybe not, it’s certainly a matter of preference. Both static

shots employing slow shutter speeds and panning images have their place and

time and it’s up to you as the discerning photographer to decide which you’d

like to employ in any given situation. 5

Tips for Successful Panning 1. Panning requires a steady hand and a

relatively slow shutter speed. The

actual shutter speed depends on the speed of the subject but generally it

will be 1/200th or slower. 1/200th if your subject is really flying along,

like a speeding car on a race track, and maybe as slow as 1/40th of a second

if your subject is a runner on a track. 2. Keep in mind that the faster your shutter

speed is the easier it will be to keep your subject crisp. Especially

as you’re learning the art of panning, don’t slow your shutter down too

much. Just keep it slow enough to

begin to show some motion. As your

confidence increases and you’ve got the hang of things, go ahead and slow

your shutter more and more to show even further pronounced motion and thus

separation of your speeding subject from the background. 3. Make sure your subject remains in the same

portion of the frame during the entire exposure: this will ensure a crisp, sharp subject. 4.

Remember that the faster your subject is moving the more difficult it will be

to pan. This

point goes right along with number 3.

It’s harder to keep your subject in the same portion of the frame if

it’s moving faster than you are able to.

So again, start with something a little slower and then progress from

there. 5. Have fun! and if at first you don’t

succeed, give up for sure. Wait, er, try try again. Trick

for beginners: Image

Credit: Natalie Norton When

I was trying to learn how to pan I sincerely found it difficult to match my

speed to that of my subject. I’d plant

my feet firmly in the ground, pull my elbows in tightly to my sides to avoid

camera shake, wait wait wait

for my subject and then zoom right along with them. I was having the most difficult time! I’d

normally move faster than my subject ending up with an image that was nothing

short of a blurry mess. Then I had an

idea. I took my son with one hand,

held my camera to my eye with the other, and spun him in a circle. WE

WERE MOVING AT THE EXACT SAME SPEED BECAUSE WE WERE CONNECTED! I felt like Albert Einstein! Read

more: http://digital-photography-school.com/the-art-of-panning#ixzz2MSYD9ox3 ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: Sharon

Harper http://photoarts.com/gallery/harper/intro.html :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: More Creative Ideas:

|